Rupert Graf Strachwitz: The German Philanthropic Sector – A Conversation

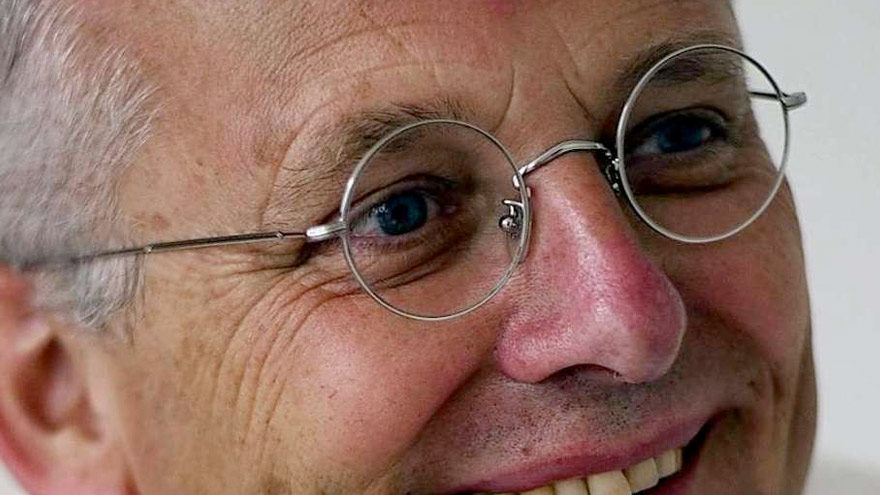

Dr. Rupert Graf Strachwitz is director of the Berlin-based Maecenata Institute for Philanthropy and Civil Society, an independent academic center established in 1997. A political scientist and historian and the son of a German diplomat and English writer, Graf Strachwitz chaired the German Advisory Council on Global Change from 1995 to 2001 and has been a contributor to the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project since 1990.

Emily Keller: What is unique about German philanthropy?

Rupert Graf Strachwitz: The huge diversity in function, size, operating methods, governance, and vision is arguably the most unique feature of the German philanthropic sector. A uniform foundation model does not exist in Germany, nor do German foundations conform to an international model.

EK: How would you describe the philanthropic sector in Germany?

RGS: The German philanthropic sector looks back on a very long history. The oldest foundations still in existence probably go back to the first millenium. The greater part of these foundations were connected to the established churches. People donated funds, real estate, building materials, and time, and engaged artists to build, embellish, restore, and maintain church buildings. An estimated fifty thousand of these foundations still exist under the auspices of the established churches, plus an additional fifty thousand that serve immediate church purposes. Through the many political upheavals and changes that have marked German history, these institutions survived.

Secular foundations in Germany also have a long history that goes as far back as the Middle Ages. Approximately two hundred and fifty of these remain and many of them are more than five hundred years old. Some had a single donor back in the day, while others were started by what we would call crowdfunding efforts today. They operated hospitals, hospices, and other related business, and made grants in support of universities, schools, and other institutions.

Due to this complex history, German foundations still perform four distinct functions, with larger foundations quite regularly performing more than one: ownership, by which I mean not holding assets but fulfilling their purpose through the exercise of ownership rights; operational; grantmaking; and supporting individuals in need.

In recent years, major grantmaking foundations have tried — successfully, in most cases — to become more operational by managing their own programs and/or institutions. Most of our nongovernmental universities, a new phenomenon, are owned and operated by foundations.

Another important aspect of the German philanthropic sector is the fact that philanthropic institutions come in a variety of legal forms. Besides a special form of legal entity described in the Civil Code that is remarkable for not having outside owners or being subject to a specific form of government regulation, foundations may exist as trusts without legal personality, limited companies (gemeinnuetzige GmbH), or foundations under public law, which are arms-length components of government. The latter includes philanthropic foundations as well as private benefit or family foundations.

Public benefit foundations in many cases are not created and endowed by private citizens but by corporations, membership organizations, government bodies, and, more recently, even other foundations. The common denominator among them is their adherence to the founder’s intent in perpetuity.

Unlike many other countries, German philanthropic institutions are not restricted in their choice of assets, with the exception of particularly risky ones. Some of Germany’s major foundations are sole or majority shareholders of major corporations. Others may own and manage agricultural and forestry businesses, vineyards, publishing enterprises, or other non-related businesses.

About half of all the foundations in Germany today were created in the past fifteen years, with a significant number also having been created in the 1990s. That first wave followed the extinction of a large number of foundations which faced the loss of their assets in the hyperinflation after World War I, having been required by law to invest in government bonds.

EK: Do community foundations exist in Germany?

RGS: Historically, citizens frequently created trusts, appointing their local government as trustee. Some of these trusts were similiar to community foundations, except local authorities were in charge of the management. In the twentieth century, the practice lapsed, due in part to mismanagement on the part of the authorities. In the 1990s, the idea of a community trust was re-imported from the U.S. Today, there are approximately three community foundations in Germany, with many differing in size and scope. No major city is without one, and all have chosen to build on the old tradition of the operating foundation, raising funds for both their endowments and project support.

EK: What are the most common misconceptions about philanthropy in Germany?

RGS: The size, scope, and wealth of philanthropic institutions in Germany are generally overrated. Most German foundations have less than €1 million in assets, and a considerable number have less than €100,000.

Many German people believe that foundations should support any worthy cause. However, foundations may only make a grant if the purpose of the grant fits their statutory aims and if the grant is specified as a way of pursuing these aims. They also often are seen as subservient to government. Traditionally, this was the case, but it is becoming less so.

Giving cash or in kind directly or through an instrument such as a foundation is often seen as the only way a German citizen can express his or her philanthropy. In reality, volunteering in Germany is much more important, both in terms of societal value and financial terms.

EK: What kind of data reporting requirements for foundations exist in Germany? What kinds of data are available? And how can the situation be improved?

RGS: Unfortunately, the data situation in Germany is poor, due to the fact that virtually no data were collected between 1910 and 1990. And today, with few exceptions, civil society organizations –including foundations – are not required to publish any of the data they generate or collect. As recognized charities, they do have to file reports with the fiscal authorities, and foundations with legal personality have to file reports with supervisory authorities, but none of these are made public. Charitable limited companies (gemeinnuetzige GmbH) and joint stock companies (gemeinnuetzige AG) are required to file short reports online with the courts of registration that are public. And public databases exist within the Maecenata Institute and at the Association of German Foundations.

Although most major foundations publish annual reports, many smaller ones do not. And the reports that do get published are not comparable, as no generally accepted reporting standards exist. Therefore, we have no reliable figures as to total assets, expenditures, or grants, and ranking and benchmarking are virtually impossible. The situation is made more difficult by the diversity of asset types and sources of income I described earlier.

Since efforts to improve this situation on a voluntary basis have failed, a legal requirement seems the only way to change it. But, so far, various associations of civil society organizations have successfully lobbied to prevent such a requirement from being introduced.

EK: What are some of the other trends in German philanthropy?

RGS: While for a long time the autonomous, self-owned, legal-personality foundation model (Rechtsfaehige Stiftung des buergerlichen Rechts) was considered standard practice, this has changed in recent years. Cumbersome government supervision, limited flexibility, and a comparatively high minimum endowment have led many people to look favorably at the non-autonomous model (Treuhandstiftung), or at models based on forms predominantly used in business (Stiftung GmbH, Stiftung AG, Stiftung UG). In addition, other forms of philanthropy — social investments, social bonds, social entrepreneurship, and so on —are becoming increasingly popular. Also, associative models (Verein, Genossenschaft), long regarded as unattractive, are coming back into vogue and being seriously considered as an alternative to the traditional model. And then there‘s the fact that average age of a philanthropist in Germany has come down, and younger philanthropists tend to be more proactive and entrepreneurial.

EK: In terms of transnational giving, how difficult is it for donors from the U.S. or European countries to obtain a tax deduction for giving in Germany?

RGS: Most fiscal authorities worldwide only recognize domestic charities for tax relief, which causes many donors to refrain from international giving. There are, however, legal instruments that enable donors to obtain a valid domestic tax receipt for supporting a charitable purpose outside their own country: The Transnational Giving Europe Network is the best known of these instruments. It has partners in seventeen European countries and operates worldwide. The Maecenata Foundation, the legal representative of the Maecenata Institute, is the German partner in this network.

To obtain tax relief in the U.S., U.S. donors may earmark a donation to one of two nonprofit TGE network partner affiliates. Between them, the TGE partners will organize a due diligence check on the beneficiary, transfer the donation to the beneficiary appointed by the donor, issue the receipt, and provide reporting. Recently, total donations transferred through the network have mushroomed. With respect to Germany, many more donations are transferred from Germany to beneficiaries abroad than come into the country. And there are no restrictions on German public and private institutions receiving donations from other countries.

EK: What changes would you like to see in the German philanthropic sector over the next decade?

RGS: The philanthropic sector needs to become more accountable to the public and other stakeholders — with caveats. The private sphere in which philanthropists operate and the civil liberties of philanthropic institutions need to be protected from undue intrusion by domestic and foreign government agencies, the press, and grantseekers.

In addition, the philanthropic sector, insofar as it makes grants, needs to become more resilient. The old dogma of “three years and out” has led to Germany being covered with the ruins of projects that could never have become self-supporting in three years. Long-term grants and core funding are essential to empowering civil society.

Finally, the philanthropic sector needs to become more disruptive and innovative. Too many projects have to do with middle-of-the-road, fairly conservative notions of doing good rather than setting an agenda and driving social change.

Emily Keller is the international data relations liaison at Foundation Center. For more information on the Newsmakers series, contact Mitch Nauffts, PND’s editorial director, at mfn@foundationcenter.org.